About fifteen years ago, I ran across this book on a vendor’s table at one of the numerous street fairs here. This was what I said about it then:

About fifteen years ago, I ran across this book on a vendor’s table at one of the numerous street fairs here. This was what I said about it then:

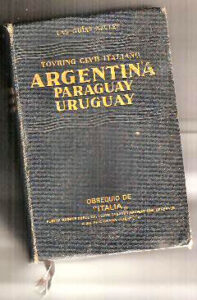

Anyone who travels extensively, especially in Europe, is probably familiar with the Blue Guide line of guidebooks. In some ways, not as “friendly” as your average guidebook, they’re packed, instead, with detailed travel information, historical notes, self-guided tours, maps, and an amazing amount of detail. They’re designed for someone who is a “traveler” versus someone who is a “tourist”, and there’s a big difference. The modern versions of those guides don’t include anything covering South America, but at one time, in their early days, they did, and by chance, while rummaging through a flea market, I found a copy of the 1932 Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay edition, in Spanish. Having just started flipping through it, I can say it’s a fascinating glimpse into a 75 year-old past, and a very different world. So, expect that over the next weeks, months… I’ll be taking portions from the touring, especially things like the historical restaurants and cafes, and taking a look at whatever happened to them, what they are now, etc. I’ve already noted that a few of the places are still in existence, and a few have moved location but are still around, and some, I know, are simply gone – it will be interesting to see…

Now, it turns out, I didn’t do that. I wandered around to a few places, but stuck the book on a shelf and more or less forgot about it. A friend’s recent find of an older book dedicated to Paris bistros, which he’s now checking out, reminded me of this book’s existence, and I retrieved it from oblivion. I decided to sort of put it to the test with a several day trip to Córdoba, about an hour and a quarter’s flight northwest of here, where Henry had to be for some folklore dance classes. I figured I could explore a new city. And to make it interesting, I decided to follow the guidance of the authors from 90 years ago. By the way, at some point, I’d contacted Blue Guides, and to correct things, they didn’t publish this book, in fact, as best anyone there knew, they’d never published guides to South America. They’d apparently leant their name, at one time, to the Touring Club Milano, in Italy, who published a series of guides for Italian travelers. No explanation as to why the book would be written in Spanish rather than Italian.

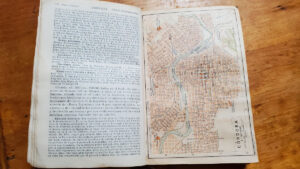

The guide is densely packed. The Córdoba section starts with listings of names and addresses for rail stations, hotels, restaurants, the tram lines, banks, consulates, a couple of important local buildings, cultural sites, and museums. No other details are given. Then a brief geographical and historical introduction to the city, along with this map (there’s a street listing with grid coordinates on the following page, plus a close-up sketch of the city center’s main streets). And then it launches into a walking tour of the key points of the city – a large number of which turn out to be churches.

There’s a lot to cover, so I’m going to break it up in a series of posts.

Mercado Sud was not on the tour, nor did it exist 90 years ago, but it was on my way from our hotel to the starting point, and you know I can’t resist a market. Unfortunately, nothing really special here, just a small, neighborhood stand type market, with no unusual things to see. Then again, as I said, Córdoba is only a little over an hour away from here, so why would there be?

The tour starts from what was probably the main arrival point in Córdoba for visitors, the main train station. Nothing is said about it other than “Starting from the beautiful Renaissance style train station…”. As best I can tell, this is no longer a working train station. The building seems to be more or less abandoned, though there are some signs indicating it’s used as an event space. It seemed more like it’s just being used for parking spaces.

Not part of the walking tour, but along the way. This is the hotel and restaurant Viña de Italia, which, of the thirteen recommended restaurants in the guide is the only one that still exists today. I don’t imagine that this is what the building looked like a century ago, and the inside has clearly been remodeled, probably around the early 70s given the style. It’s also no longer a fancy hotel restaurant, it’s just basically a hotel lobby bar with sandwiches, salads, and some pastas. I had originally thought to eat there, thinking it might still be a top local restaurant, but, given that it’s not, I didn’t.

A short two blocks away, the first church, of many, Templo del Santísimo Sacramento, where the “ojival” style architecture is noted. That was a new word for me in Spanish, and turns out to be the same in English, and refers to the pointed archways, rather than rounded ones. The octagonal cupola and the two bell towers are also pointed out.

One of the issues I had with this guide was that at times, it fails to mention when you need to divert off what seems to be the pathway to see something of note. I have the feeling, given the character of the neighborhoods I passed through, that some of these streets were simply not built up 90 years ago, and you’d be able to see your next destination without obstruction. Our next stop is the San Roque church and plaza. Of note, apparently, the altar inside the church is (or was) supposed to be a stunning construction of wood and gold, but, probably pandemic related, virtually every church in the city was closed except for Sunday masses and/or by appointment, so I was not able to enter most of them. The plaza in front, at the time of the guide, featured a bust of Ramón Gil Barros, a famed physician in Córdoba who was both the dean of the local university medical school, and mayor of the city. That bust is gone, and there’s one of Bishop Diego Salguero y Cabrera, who apparently paid for the building of the church in 1761.

Next up, the original Banco de Córdoba building, which now seems to double as an exhibition space and museum… again, not open when I passed by.

Having apparently covered everything of interest to the east of the city center, the tour moves on to the central plaza, San Martín, dominated by a statue of General José de San Martín, the “liberator” general of the army that overthrew the Spanish and liberated Argentina, Peru, and Chile in the early 1800s. The statue itself is a copy of the one in Buenos Aires, though the base is a different design.

At the time the guide was written, this building on the plaza was the central police station, and had formerly been the city hall. These days it’s a cultural center bordered by some shops. I’m guessing the façade has been updated a bit since the building was built in the late 1700s.

Next door, the main cathedral, described in the guide as “colonial style”, and dating from the mid-1600s. Noted are the octagonal cupola towards the back, and apparently inside, quite the statue of Christ the Redeemer. The cathedral was closed other than by application to the secretary’s office – given my limited time, I decided not to try to convince them that entering for the purposes of snapping a few photos was a valid approach.

The passageway between the two buildings, Santa Catalina, apparently used to house the natural sciences museum at the back of the former police station, though the given address is now a small municipal library. There’s also a small gallery devoted to the “dirty war” period of the late 1970s/early 1980s, listing the names of all locals who were “disappeared” in the form of two giant fingerprints.

Not existent at the time of the guide, there’s now a statue behind the cathedral of Jeronimo Luis de Cabrera, the founder of the city of Córdoba, in 1763.

Reversing course to the plaza and the other side of it, we head to what was originally the Casa del Virrey, or Viceroy’s House, had, by the time of the guide been turned into the Sobremonte Museum, which it still is. It was also one of the few museums in the city open. Mostly it’s staged rooms of the Viceroy’s time period, along with displays of domestic artifacts (fans, combs, furniture, pianos) collected together. It was important enough at the time for the guide to devote two pages to it, along with a detailed floorplan, more words than any other spot noted in the city.

And, back across the plaza to the San Merced church, particularly noted for its tilework on the bell towers, though from down below, it was barely visible.

We then head to the Santa Catalina church, now a monastery, at the end of the passageway off the plaza. It was noted for its interior “Latin cross” style – again, not accessible right now.

And, on to the Santo Domingo basilica, which is also noted for the tilework on its cupola, much more visible here.

Passing by the Caja Popular de Ahorros, more or less the main savings bank at the time, it’s now the headquarters for the provincial lottery.

And finally, ending up circling back around to the south side of the plaza, and getting ready to head to points south (next post), this building was identified as the Convent of Santa Teresa. Most of the building is now a religious art musuem (not open), though a part is still a convent, however, now a Caramelite one, dedicated to San José.

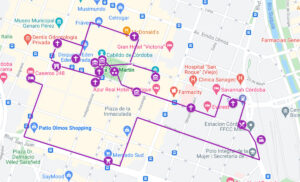

A quick map of the walk – starting from our hotel on the far west, and then sort of counter-clockwise, down to the market, and then over to the far eastern side at the train station, and then a sort of zig-zag back to the final point just south of the plaza. This is where I stopped for the first day’s part of the tour. I’ll continue with the rest over a couple more posts, and then finish off with one dedicated to food, of course.