When it comes to pasta, I tend to like simple. It lets both the pasta and a couple of clear ingredients shine through. At the same time simple pastas are often the hardest to get right, because, as the adage often goes, any mistake is really obvious. If you’re making a complex sauce, like a ragú, and you change, add, or subtract an ingredient, or alter the proportions of ingredients, while it might not taste like the recipe you’re working from, it’ll probably still come out delicious. There are enough ingredients melded together that things even out. When you have two or three ingredients, missteps are almost always noticeable.

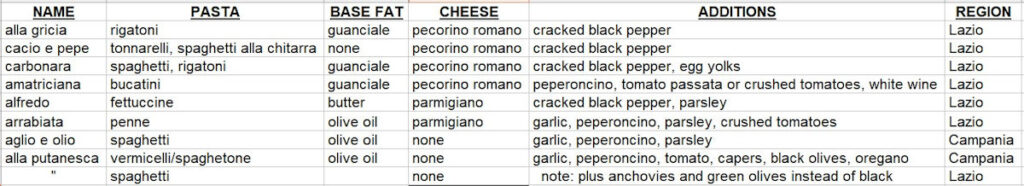

I’m going to start with this little chart that I put together (and you can click on it and blow it up and save it for posterity if you like). These are the four classic pastas of Rome, plus an additional one that’s more of a modern take on a very basic classic, as well as a couple from neighboring Naples, and one sort of caught in between. If you look at them as all related, and follow the same basic steps to make them, they’ll start to make sense. I could probably extend this across the twenty regions of Italy and their classic simple pastas.

Although outside of Italy it’s probably the least known, pasta alla gricia is the oldest of them all. The recipe for it can be traced back to roughly 400 C.E., over 1600 years ago. Recipes for the others don’t appear until much later, and that fits with some of the ingredients, particularly tomatoes, which didn’t really enter Italian cooking until the early 1800s, and black pepper, which a) was not in the original gricia recipe, and b) only started to appear around the same time as cacio e pepe, when pepper started to be readily available in European kitchens (as opposed to a luxury item for the wealthy) around the late 7th century.

There are debates about how gricia got its name, from fanciful ideas that it’s a play on grigio, for grey, because guanciale turns grey when it’s cooked (it doesn’t), to the idea that it’s an invention of the hamlet of Grisciano, a bit north of Rome. Given that even today the town has a mere 131 residents, and 1600 years ago was probably no more than a couple of houses on a hillside, plus, language-wise, the pasta would then likely be called alla grisciana. The most likely, though unproven origin, is that the name comes from street vendors, who at the time were called gricios, and served up simple dishes from stands or in front of their homes. And, their name comes from their origin in the northern part of Italy, at the time part of a canton of Switzerland, Grigioni. A pasta made by your local gricio would be alla gricia.

A note, when people talk about the “four spaghettis of Rome” they’ve got it wrong, it’s the “four pastas of Rome”, because actually, none of them traditionally use regular spaghetti. For pasta alla gricia, we have four ingredients. The pasta, most classically rigatoni or another wider, shorter pasta; pecorino romano, an aged sheep’s milk cheese; guanciale, a salt and herb cured pork jowl, or cheek; and black pepper. You’ll need a large skillet, a pot for boiling water, and some salt.

Options if you have trouble finding these? The pasta, again, anything wider and shorter is fine. Pecorino – you kind of want that slight tanginess of sheep’s milk, so maybe another sheep’s milk or goat’s milk grating cheese, but in a pinch, parmigiano or something similar would be fine. Guanciale, it’s pretty unique, and once you’ve tried it you’ll understand, but classic Italian pancetta would work as it’s also a salt and herb cured pork, just from the belly rather than the cheek, and different herbs. I wouldn’t use bacon, because it’s usually smoked, and that’s a whole different flavor, but if you can find cured bacon or pork belly that isn’t smoked, that would be similar.

The guanciale is sliced about 1/4″ thick, and then sliced across into small pieces, allowing that each piece has a layer of meat surrounded by fat. We’re going to cook it over the lowest heat, just slowly rendering the fat out of it, and then gradually letting it brown in its own fat. There are arguments over whether to add some pepper at this stage or not, some saying it should only be at the end. I do it at both, putting a few grinds of pepper with the guanciale as it renders.

This is the chef’s secret on getting the emulsified cheese right on all of the above that use cheese. You know you’ve done it, I’ve done it, where the cheese gets all stringy and clumps up when you add it to the pasta. This and one other tip which we’ll get to, prevent that. As your pasta is cooking, you get all that starchy water that you’ve probably heard you should add to the sauce of any of various pasta sauces. You should add it to the cheese too. Not much – this was about a cup, grated, of the pecorino, and maybe two tablespoon of the hot, starchy water, whisked together with a fork or spoon to make a creamy mass, sort of the texture of cream cheese.

And, the pasta. You’ll note I’m not doing this in a huge pot of water. For years people talked about using lots and lots of water so that adding the pasta barely lowered the temperature. And for years, it would take forever after adding the pasta for the water to come back to a boil. Until someone pointed out to me, as I’m doing for you, that the smaller the quantity of water, the fast it will come back to a boil. The pasta isn’t really chilling anything down, unless maybe you’re throwing frozen ravioli into the pot, it’s just interrupting the boil. It’s also much starchier this way, which is really good for thickening your final sauces. By the way, I use a ratio of one tablespoon of coarse salt to one liter of water.

Your guanciale is rendered and brown and crisp (if it’s ready before the pasta, just move it off the heat). Cook the rigatoni for about two minutes less than the recommended time on the package. Since this was fresh rigatoni from a neighborhood shop, that meant after about three minutes of cooking, but with dried pasta you’re probably talking about ten minutes. Read the package. Add the rigatoni and some of the pasta water to the pan with the guanciale. It shouldn’t be swimming in liquid, better to start with one ladleful of the water and add more if needed. It’s enough so that as you toss and stir the pasta into this rendered fat and starchy water (doesn’t that sound appetizing?) combo, the pasta finishes cooking and the water and fat emulsify and form a sort of creamy mixture…

…that looks a lot like that. You want to end up with somewhere between 1/4 and 1/2 a cup of liquid left in the pan.

Remove the pan from the heat. Don’t just turn the heat off, get it off the burner. This is key, really, it is. Add the pecorino “cream” and immediately start to toss and stir this so that it emulsifies right into that remaining starchy liquid.

If you’ve done it right, the pan and pasta both will be coated with this thickened cheesy liquid. I won’t say more about what it looks like, but use your bedroom imagination. And hey, good pasta is sensual, right? I know, I know, you won’t be able to get that out of your mind now. Pasta. Sex. It’s all good.

Grind more pepper over it – I like a lot of pepper, so I used maybe twenty grinds over the top. Then toss it all together.

And, serve.

This is the general process used for making all of the pastas in the chart, just with some different ingredients. I’m solo-ing it for August, so I’m going to be playing with all of them over the next couple of weeks, and I’ll probably just refer back to some of the steps here.

[…] had the feeling that there were folk out there who wanted to really see some of the basic steps of making simple pastas. I hadn’t expected quite the response I got from folk who sent me messages with thanks for […]

[…] talking Spaghetti alla carbonara here. If you start from alla gricia, the only difference between the two is the egg. Instead of subtracting an ingredient, guanciale, […]

[…] dish is about 100 miles northeast of Rome. The dish, like the others we’ve been exploring, is based on that original gricia, with cured pork and cheese being the core ingredients of the “sauce”. Over […]

[…] the four famed pastas of Rome, and their family tree connections. A quick reference back – gricia, cacio e pepe, carbonara, […]