This sounds like the title of a novel that might have been written by one or another fantasy writer in the realms of dragons, elves, monsters, and heroes. But, it is a reference to a very obscure pasta from Sardinia. Specifically, from the 800-person town of Morgongiori, on the slopes of Mt. Arci, in the southwest part of the island. Here, a traditional pasta shape was born over half a millennium ago, and has been faithfully made by the locals for All Saints Day, November 1st. These days it’s also made for other festivals, though only by a few remaining local women who are trying to maintain the tradition of this “endangered pasta”.

The noodle in question, the lorighitta, a simple twisted ring of dough. The origin of the name is a little lost, with the word, while referring to some sort of ring in the Sardinian language, variously being touted as being a likeness to the iron rings that horses were tied up to, the yoke around the neck of an ox, or the earrings of a young bride. To be upfront, this is a pasta I’ve never had in situ, nor, actually, anywhere. I’ve seen photos, I’ve watched videos, but I’ve not up and made the trip to Morgongiori for the Halloween weekend just to try this dish. Nor am I likely to. But I’ve read enough different recipes to get a solid feel for it, and hopefully, I’ve recreated it reasonably well. I’m also trying to make up for those weird looking and off-colored black carrot lorighittas from the previous post. Side note, the plural is lorighittas not lorighitte, which would be the Italian way of pluralizing it, because the Sardinian language uses “s” to form plurals.

The dough is a simple one – semolina flour, water, and a pinch of salt. The traditional ratio is 2:1 flour to water, and that results in a nice, smooth and soft dough. Since I was making this just for us, I used a cup of the flour and a half cup of water – in retrospect I’d probably make a bit more (1½ cups of flour and ¾ cup water), as it turned out to be about three decent portions and four would have been better. Kneaded for about ten minutes.

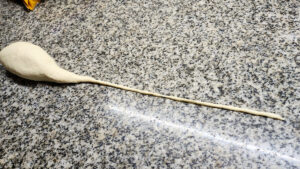

Now, this appears to be the classic approach to rolling this out, using your palms to create a long thin strand off the main bulk, and then, as you’ll see, wrapping it around your fingers and breaking it off at the point that just completes the two rings. I found this to be tedious, and based on a couple of videos, so do others. Once I figured out how much dough it took to get the right length strand, I simply pinched off balls of dough in that amount. Much easier.

So the size you want is enough to wrap around your three middle fingers. Of course, everyone’s hands are different sizes, so that’s a nebulous ring size. Such is life. Pinch it off, and then seal the two ends together, along with the other loop, to create a sort of anchor point. Then, and here I should have set up the camera on a tripod and maybe videoed it (though you can find many folk who have done so), with one hand you hold the anchor point steady, and with the other, you “wind your watch”. Basically just twisting it in one direction to create a braided look.

It takes a little practice, but you can see the twists come from the anchor point. I find myself curious if there’s a traditional number of twists these should have. I didn’t find anything online, but it seems like the sort of thing that, given the religious holiday these were made for, probably exists.

Needless to say, these are tedious to make. In terms of how I went about things, I actually got the ragú started first, and then while it was simmering away for an hour, combined and kneaded the dough (15 minutes), let it rest (10 minutes), rolled it out and shaped it (30 minutes), and got a pot of salted water boiling. I imagine with practice it wouldn’t take me quite so long to shape these.

As best I could determine, lorighittas are served simply with either a sugo di pollo ruspante, which literally translates as free-range chicken gravy, or the same sauce just without the chicken – presumably for those now and then years when All Saints Day fell on a Friday, and chicken was not to be eaten.

There’s a common dictum that Italians don’t eat pasta with chicken. And, for the most part that’s true. Theories abound – chicken was a premium meat and only the rich ate it, chicken was poor people’s food and anyone with money would use pork, chicken has a texture to similar to pasta, chicken has a texture that’s too firm for pasta, etc., etc. No one agrees as to why. There are exceptions, though I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a pasta and chicken dish where the chicken was diced or shredded like we might well do in an American pasta. And, there are definitely exceptions for the offal – various dishes that use livers, giblets, cockscombs, and the like. But I think all of the few that I’ve encountered, like this one, the chicken pieces are left whole, and in a sense the dish becomes a chicken dish with pasta more or less on the side, tossed with the sauce the chicken was cooked in.

We have chicken thighs and drumsticks, skin removed (four of each, as I was intending this to give us two meals apiece). Just under a kilo of tomatoes, pulsed a few times in a blender or food processor. A half cup of white wine, a chopped onion, a couple of chopped cloves of garlic, and some fresh sage, rosemary, and bay leaves. Salt, pepper, and olive oil, of course. Also some sardo cheese – for this quantity I had about half a cup of grated cheese.

I’m going to skip some steps visually. In a splash of olive oil, sauté the onion and a good pinch of salt over low heat until it’s transluscent and just starting to color. Add the garlic and cook for just a minute. Add the chicken and cook for a few minutes on each side just to give it a little color. Deglaze with the white wine and let that cook down until it has reduced by about half.

Add the herbs, tomatoes, and a few grinds of black pepper. I’m not going to add salt at this point because this is going to cook down until thick, plus have pasta water added, and I don’t want it to get too salty. Bring to a simmer and then turn the heat down to very low.

And, let it cook for an hour. The chicken will be falling off the bone tender, and the sauce should be well reduced. This is a good moment to drop your lorighittas in the boiling salted water.

Remove the chicken and keep it warm. Remove the branches and larger leaves of the herbs and throw away. Turn the heat up and add a ladle of the pasta water, to help emulsify it. This is a judgment call, add another ladle if needed. You want a thick, rich sauce. Keep in mind that the pasta water is adding salt to the sauce. So this is the point to taste it and see if it needs more salt. It’s also the point to add in some freshly ground pepper – I added a fair amount.

Initially, the lorighittas will sink to the bottom. Give it a stir to make sure they don’t stick to the pot. After a couple of minutes, when the water returns to a boil, they’ll float. At this point, scoop them out and add them to the sauce, along with a good amount of grated sardo cheese – which is basically a pecorino made with cow’s milk instead of sheep’s milk. Pecorino will work too.

Finish cooking the pasta in the sauce for another couple of minutes.

And, serve a portion of the lorighittas with a drumstick and thigh. There will likely be some extra sauce in the pot to spoon over the chicken.

To the best of my knowledge, this is a pretty faithful version of Lorighittas al sugo di pollo ruspante.

And, damn it’s delicious. We’ll be making that again.

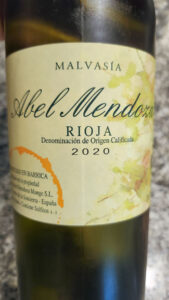

There are three really classic white grapes from Sardinia – Vernacchia, Vermentino, and Malvasia. There are a few others as well, but these three are seen most often, at least outside of Sardinia itself. I wasn’t able to find a Sardinian, or even Italian, version of any of the three, nor a local Argentine one (not sure if any of those three are grown here). But I did find a white Rioja made from 100% Malvasia and picked up a bottle. Perfect accompaniment for this dish! My description on Vinvino: “Pale yellow, clear rim, thin legs. Aromas of green almond, quince, grapefruit. Medium body, moderate acidity, upfront note of cream, grapefruit pith, followed by quince and almond. Long finish where vanilla from oak rears its head.”